Over the last 60 years, more than 350,000 tons of high-level nuclear waste has been amassed the world over. This material must be deposited for thousands of years in a safe place, i.e. one that will not harm humans or the environment. However, such a repository has yet to be created and the production of nuclear waste continues unabated. Swiss-based nuclear physicist and internationally renowned repository specialist Charles McCombie and some of his most important allies provide director Edgar Hagen with insight into their persistent struggle to find the safest place on earth in order to resolve this grave dilemma.

On this quest, the film travels the world, encountering a diverse range of people and places – including a heavily populated area in Switzerland, a nomadic family in the Chinese Gobi Desert, a sacred mountain in an Indian reserve contaminated by nuclear waste and demonstrators in Gorleben’s forest in Germany. The film witnesses the secret arrival of a nuclear waste cargo ship in Japan and observes volunteer communities in the UK at a meeting on nuclear waste disposal. In all of these places, reason, democracy and scientific integrity are put to the test by practical constraints, strategies and fears. The film pinpoints a number of appealing options: a mayor in New Mexico is prepared to store the most dangerous substance on earth in his community for large sums of money. Scientists investigate a vast, flat area in the Western Australian outback that could potentially be used as a repository for high-level nuclear waste from across the globe. Edgar Hagen’s film raises a huge range of questions about how we are dealing with the situation today and our responsibility to future generations. If there is no other choice, is it possible to force through such a project against the wishes of local residents and, if so, is this a wise solution?

JOURNEY TO THE SAFEST PLACE ON EARTH is a divisive undertaking, leading us to the ends of the earth. Over the course of the film, it becomes clear that there is no quick fix to this conflict. JOURNEY TO THE SAFEST PLACE ON EARTH throws doubt on our established views of the world and takes us to the limits of knowledge and social responsibility.

Interview with the director

Vadim Jendreyko: What motivated you to make a film about creating repositories for nuclear waste?

Edgar Hagen: Very few films have explored the various dimensions of the topic of atomic energy, even though it’s all around us. We are in a state of complete denial. The media reports on it all the time, but it’s such a vast issue and so closely intertwined with power that it always left me with this sense of powerlessness. The key question for me was: how can I address this topic without feeling so powerless. We’re dealing with closed-off sites, time periods spanning hundreds of thousands of years, monitoring systems, the police and the military. The substances and the technology are far too dangerous to be freely accessible; they must be protected. It is a sealed-off, secret world in the midst of our society, not unlike a freemasons lodge. Is it even possible to have a normal conversation about it? Does it have any kind of human dimension and can I explore this topic in a film, faced with the knowledge of my own powerlessness? These were the thoughts going through my mind and the challenges I faced.

VJ: You’ve addressed being in a state of denial in other films. Is it also a key topic in this film?

EH: Yes. And I discovered that this state of denial is not a problem restricted to any particular country. People in very different countries with various political structures have very similar experiences and face the same dilemma. So I was looking for a figure who was up to the task of dealing with this international dimension – who would go to the ends of the earth to find a solution – and then I found Charles McCombie.

He actually takes a very pragmatic approach to finding a solution. The industry, the scientific community and the political sphere expect this from him. He rises to the challenge: a country needs a repository? Okay, I’ll find you one. He researches how this can be done and then tries to prove that it’s possible. For me, this isn’t the ideal approach; it’s a pragmatic one. It has nothing to do with good and evil. He operates outside of the boundaries of good and evil because he does what he believes is necessary for society as a whole. This leads us to the following question: where will we end up if we simply continue going down this road?

I knew that I wasn’t interested in looking at outdated concepts, such as the idea of rocketing nuclear waste into space, or in scandalous procedures like those used in Russia, where huge amounts of high-level waste are temporarily stored in hair-raising conditions.

I wanted my film to focus on the most advanced and credible projects to deal with nuclear waste and Charles McCombie is an authoritative and high-profile representative of this type of repository.

VJ: What fascinates you about your film’s lead protagonist?

EH: The interesting thing is that we don’t belong to the same ideological camp. The first time we met, we agreed that we would treat each other with respect and not focus on our differing viewpoints. That also means that I have to respect his belief in this technology and this industry. He’s open to being confronted about his ideas and more than ready to “argue his point”.

VJ: Has he seen the film?

EH: Yes. He always said: “If I made a film, I would make it as controversial as possible.” That it was important to portray the controversies he’s embroiled in as part of his work. This is nothing new for him: he’s operated in this “conflict zone” for decades. He develops a repository project, tries to realise it and the project collapses because some unreasonable group or other – from the perspective of the industry – does something to prevent it. This means that McCombie and his projects have come up against countless obstacles. This is the reality of his work and he has no problem with the film portraying these obstacles.

VJ: Turning an exciting idea into a film is a long process. Can you describe how you put your idea into practice?

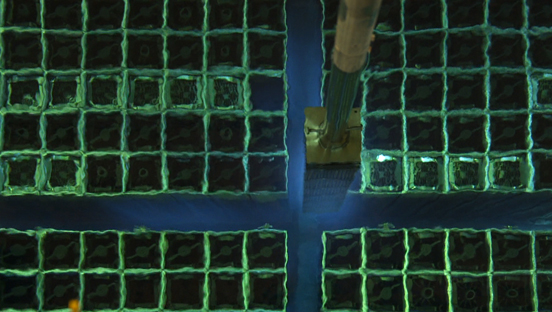

EH: It was a real challenge to tell the story from two perspectives: On the one hand, the official viewpoint of the industry and government and, on the other hand, the perspective of the opponents and critics of atomic energy. Most importantly, I had to know what I was talking about. This didn’t mean becoming a physicist, but I did need an in-depth knowledge of the various aspects of the problem. It’s a very complex field. I needed to meet and interview a lot of people. The challenge while shooting was gaining access to the sites we wanted to film. While we were researching the film in 2010, for example, we were allowed into the reprocessing facility in Sellafield and did a test shoot. We managed to film there for two days, even if we weren’t allowed to see a lot of things. “For security reasons”, they told us. The cooling ponds, for example – vast cooling ponds containing spent nuclear fuel, some of them still out in the open air at Sellafield. When we wanted to come back to film in 2012 after the reactor disaster in Fukushima, everything was sealed off. They weren’t letting anyone in anymore. Another example is Nagra, the Swiss organisation for the disposal of radioactive waste. I tried to get in contact with them again and again, but was fobbed off every time. I wanted to visit Sweden and Finland with a group of parliamentarians. They withdrew my invitation twice.

VJ: Why do you think this is?

EH: The nuclear power industry in the West is really on the defensive. This isn’t the case in China at all: there’s a sense of a new nuclear era, just like there was here at the beginning of the seventies. Perhaps the Chinese thought we were some kind of propaganda organisation for the western nuclear power industry. At any rate, we found them relatively open and approachable and we were the first western film crew to be allowed to film on building sites and in the control room of a nuclear power plant and to travel to the planned location for the deep nuclear repository in the Gobi desert.

VJ: I noticed that there are barely any women in the entire film. Are these technologies and their consequences more of a man’s domain”?

EH: Yes, it’s not a film about women – it’s a film about men. It looks at a very male-dominated world, which evolved from the military sector. We’re dealing with a masculine form of power and now we have to address its legacy. If we look at the opponents of atomic energy, we get a different picture of a much broader spectrum of society. While making the film, my sole focus was the debate and at the end I was a little shocked to realise that it only featured men. Our approach to nuclear technology today clearly requires a masculine mindset. Women are able to adapt to this, of course, but ultimately it is more typically male.

But it’s important for all of us to understand the trouble that this particular type of masculine behaviour has got us into. I find it interesting to watch these men now and observe how they deal with this manmade situation. If you focus on a particular way of thinking, you also reveal its limitations. What we see is actually a group of powerless men. So it seemed logical to me to keep the focus on men.

VJ: There are currently 300,000 tons of high-level waste worldwide and more is being produced every day. Regardless of whether we’re for or against atomic energy, we can’t deny the fact that this waste exists. What’s your outlook on this?

EH: In the film, the Swedish expert Johan Swahn says that above all we have to make sure we don’t do anything stupid. So if we’re not sure – and until now no one has come up with a safe concept – we shouldn’t do anything that can’t be reversed and dispose of the waste in a way that means it’s no longer accessible. I share his view. My message is: we have to address these issues. Each person has to do this in their own way and with the means available to them. We need people to address these issues, we need transparency and it’s important to talk about this topic with a certain openness. This means we have to create a more open discussion to be able to – and “solve” is the wrong word here – to make any progress at all with this problem.

VJ: You said that it’s important for people to admit their insecurities.

EH: I think that’s the sign of a strong society. If you believe in democracy or in an open society, then this is the only way. Nuclear waste is just one example of many. There are a lot more skeletons in the closet. How we treat our resources, for example. How we will have frittered away our raw materials in two to three generations, what we’re extracting from the depths of the earth and what impact this has and will have on our lives. There are people investigating climate issues who are coming to devastating conclusions. Ultimately, we have to ask ourselves: do we have a vision for the future at all? I believe that this is the underlying question. What do we actually believe in?

VJ: The film depicts a certain helplessness on the part of the scientists. No matter what continent, they all hit the same obstacles.

EH: We travelled around the world and visited the places with the most serious projects. We left Finland out because they follow the same approach as in Sweden: They’re drilling into the granite bedrock – in Scandinavia there is only granite – and water flows through this rock. This means that they have to use copper canisters. Not because of the radiation, but to stop the water from coming into contact with the fuel. But we don’t know how long the copper casing will stay airtight.

VJ: How are we planning to find this out?

EH: I don’t know. In the film, the Chinese scientist Ju Wang says: “We’ve conducted experiments over very short periods of time to forecast what would happen over very long periods.” Ju Wang is the only person in the film to point out that we are dealing with millions and not hundreds of thousands of years. A Chinese person highlights this problem. This is possibly because he is a geologist who doesn’t have his roots in the nuclear power industry and is dedicated to properly addressing these issues.

VJ: What kind of time periods are we talking about then?

EH: The radioactive decay of radionuclides is calculated in half-lives. After one half-life, the radioactivity is only half of the initial value, after two half-lives, a quarter, and so on. The half-life of plutonium is 24,000 years. It remains dangerous for many times this period. Highly radioactive nuclear waste from nuclear power plants is always a cocktail of different waste materials, whose half-lives could span many millions of years. On top of this, we have chemical reactions, which are hard to predict. There’s no way to be completely sure about what will happen. For example, in Hanford in Washington State, liquid waste is stored in countless steel barrels which are corroding and leaking and no one knows exactly what they contain and what is going on inside. The chemical cocktail is seeping into the groundwater, into the Columbia River, which flows through the whole of Washington State going as far as the border to Oregon and finally into the sea.

VJ: Is there a positive message in the midst of all this helplessness and powerlessness?

EH: The positive message is: we have to address this problem. We need structures, we need transparency. We need young people to get involved. After all, a final repository can’t be realised overnight. This demands an incredible level of expertise, so we need people to dedicate themselves to this issue: geologists, scientists and non-partisan politicians, who question the information provided by researchers, and a society that keeps an eye on these people.

VJ: So the positive message is the impetus created by this challenge? The impetus to take decisive action and confront this situation, to stay curious and open-minded and to adopt a constructive approach?

EH: Yes, so that we say: wow, that’s a crazy situation we have to face there. What a challenge!

VJ: Did you find the safest place on earth?

EH: It sounds like the title of a Jules Verne novel. It holds a promise. It is a promise that we’re constantly making as a society without knowing if we can actually keep it. Ju Wang touches on it in the film when he says: “Don’t say: the safest place on earth. Say: one of the safest places.”

VJ: This interview has made me see the title in another light: the safest place on earth is the space within a civil society where it addresses these topics. Not somewhere deep down in the earth, but in parliament or in a public discussion because these things are dynamic and also last longer than copper.

EH: Yes. That means we have to keep the lines of communication open – we can’t just blindly trust those in charge. We have to maintain a critical and lively dialogue.

VJ: You appear in the film. Why did you opt for this approach?

EH: I realised that I couldn’t leave the protagonists on their own in front of the camera. After all, I didn’t want to present these people, I wanted to experience them “live” with all their contradictions. It also demonstrates my goal to communicate with the people involved on a level playing field. My voiceover is an extension of this. After I’d decided to narrate my film from this perspective, I had no choice but to take this approach. I wanted to create a contrast between something vast and something small.

VJ: Do you mean between the vast topic of atomic energy and an ordinary person?

EH: Yes. That’s why it was also important for me to ask direct and simple questions in the film, to show what happens when you approach such a huge topic with a simple question. That’s all the film does, really: it looks for answers to simple questions and I overdo it a little to get my point across.